An excerpt from an unfinished novel…

by Martin Bannon

Chapter 1

I slam on the brakes and begin to count. How many seconds will it take for Mrs. Yee to sail from the aisle seat of the third row into the windshield? If she leads with her head, will she merely shatter the glass or punch a hole in it and sail clean through? I wonder if that’s a survivable injury. But it probably doesn’t matter, because at sixty miles per hour the bus will travel at least another hundred feet before coming to a stop. In the process, five of its ten wheels will knead what’s left of her into a lifeless mass of doughy flesh.

My daydream is interrupted by a shout.

“Hey, driver! You miss turn!”

I check the mirror. The admonishment comes from the woman in row three that I’ve dubbed Mrs. Yee. I don’t know her real name. I never know any of their names. The Chinese passengers don’t consort with the bus driver. They only speak to me when something is wrong. Like now.

I realize my mistake. I’ve just passed the freeway exit that would’ve taken me to my last stop of the night: Soulong Tours’ Chinatown office on Stockton Street, where the last eight passengers on tonight’s run boarded fourteen hours ago—and where they have a reasonable expectation of being returned to. Only now I’ll have to go two miles out of my way. Which sucks, because it’s nearly 11 PM and I still have to drive back to the bus yard in Oakland.

“You bad driver!” Mrs. Yee scolds. “You miss turn.”

I glare at her in the mirror. No point in brown-nosing this crowd. The Chinese passengers never tip. Not even if they’ve cleaned up at the Reno Hilton’s Pai Gow tables. Unless you count the orange that once fell out of a woman’s pink plastic bag and rolled down the aisle toward me. When I attempted to return it to her she waved me off. Maybe it was a tip. More likely, she thought it unfit to eat.

The only tip I ever got from a busload of Chinese tourists had nothing to do with my thrice-weekly gamblers’ runs. It came from a group of Taiwanese beauty school students I was assigned to shuttle around San Francisco for a week. Except for their chaperone, they spoke no English. And the only Chinese I spoke were the three phrases I learned for the occasion: good morning, thank you, and goodbye. Not much, but still enough to set them tittering each time I spoke. It was probably my mispronunciation that made them giggle; whatever it was, they thought it was worth a twenty-dollar tip.

I pull off at the Fifth Street exit and begin making my way back toward Union Square, beyond which the Stockton Tunnel serves as a gateway to Chinatown. Hee Kwan’s Soulong Tours is just one block farther. The tired and cranky passengers—gamblers, having lost all their money, are always cranky on the way home—are already on their feet by the time I roll to a stop. The women are, at least. Some of them are still trying to rouse their sleeping husbands.

I set the brake, open the door, and hop down the steps to the street just seconds ahead of Mrs. Yee, who’s coming at me with a menacing look.

“Good night. Thank you for traveling with Soulong,” I say in a rote impersonation of a pleasant person.

“You still bad driver,” Mrs. Yee mumbles as she alights to the sidewalk without looking back.

Her husband follows without comment, as do the other six gamblers. One man manages a quick nod in response to my canned thank you. I waste no time in hopping back into the driver’s seat and closing the door. If there’s an upside to turnarounds, it’s that I don’t have to handle luggage.

Within minutes I’m back on the Bay Bridge—the lower, eastbound deck this time. I struggle to keep my eyes open for the fifteen minute ride back to the bus yard in West Oakland. My day, too long by half, began at five a.m. this morning when the phone rang.

Not my phone, but the sixty-year-old dial model affixed to the wall in the drivers’ room where I spend my homeless nights, trying to sleep on a mattress thrown across two old metal desks. This is the arrangement I’ve made with my employer, Giton Charter Service. I keep my backside dry and reasonably warm in exchange for being on-call twenty-four-seven.

This means that when a driver oversleeps and fails to show for his early-morning commute run or Reno turnaround, I get the call. When Hee Kwan adds another bus at the last minute, I get the call. Or when a driver gets into a shouting match with the company’s owner, Mr. Giton, and walks off the job, I get the call. Whatever the reason, I’m off my mattress, into one of my three shirts and my only pair of pants, and firing up a bus within ten minutes. In dispatcher’s terms, I’m what passes for instant gratification.

Not the cushiest of jobs, but it beats sleeping on trains and in self-storage units, which is what I was doing when Mr. Giton suggested this arrangement. I’d only been driving for him for six months when I ended up on the street, due to a misunderstanding with my roommate. The guy also happened to own the place we shared, so he held all the cards when “the unfortunate incident” occurred. He tossed me out and kept my deposit to cover the “emotional trauma” I caused him.

Just talking about it gets my juices going. If I’m not careful, it’ll happen all over again, despite my best intentions. You see, I have a condition.

Chapter 2

“Good morning, Mr. Peaslee,” Miss Mary says through the two-inch security glass—a West Oakland staple—as I walk into the office on Friday following my Marin County commute run into the City. Nobody seems to know Mary’s last name; she’s just Miss Mary.

And she’s the spindle around which the Giton record turns; nothing happens in this company without her. To the drivers, she may as well be the company. She hands out the dispatch assignments and the paychecks—the only two things a driver needs to care about. And if you were foolish enough to make a complaint, it would be to Miss Mary as well.

“Morning, Miss Mary,” I mumble. At least, that’s how she would characterize my speech, if she were the kind of person who engaged a person socially. Everyone says I mumble. But not Miss Mary. She doesn’t have time for idle conversation.

“Here you go,” she says, passing my paycheck through the cashier slot in the security glass without my having to ask for it.

“Thanks.”

“And I have an overnighter for you tomorrow, if you’re available,” she says.

I laugh.Miss Mary does not. Miss Mary never laughs. Except in my fantasy.

She’s sitting on a stool near my makeshift bed in the drivers’ room. I’m telling her a story from my childhood. There are tears running down her face and she’s begging me to stop. She wipes them with the hem of her skirt; then she blushes when she realizes she’s exposed her slip to me. She drops the skirt immediately. “Oh, please, Mr. Peaslee. No more!” she begs. “I’m sore from laughter.” But I don’t stop. Her laughter comes in gasps and she crumples to her knees in front of me. She throws her hands over her ears and screams. “Stop! I can’t go on,” she pleads. “You are killing me.” And I do stop. Without looking back I walk out of the room and down the stairs, leaving her heaped on the floor in her tear-stained indignity.

I see Miss Mary’s brow tighten ever so slightly. “I’m sorry for laughing, Miss Mary. But you know I’m always available. Where else would I be? I live here.”

“I know nothing about your personal life,” Mr. Peaslee. “That’s your business.” Her tone is matter of fact, but not unkind. “Am I to take it that you’re accepting the assignment?”

“Sure. I don’t turn anything down.” I start to add “you know that,” but catch myself. Miss Mary would assure me that she knows no such thing, and doesn’t want to. She’s all business, all the time. “The usual?” I ask, assuming it’s a Reno run.

“No,” she says. “It’s a Tahoe trip.”

Wow. The senior drivers always take Tahoe. They’ve never given one to me, the only white driver in an all-black company. I can’t imagine what this means. Until Miss Mary continues.

“You were requested,” she says, answering the question on my face.

“Requested?” I say, looking at my shoes and realizing they’re in desperate need of polishing. I look back at Miss Mary. “By who?”

“It’s a private charter out of the City. The pickup is in Noe Valley at seven.”

I want to ask who the client is, but I know she won’t tell me. And it really doesn’t matter anyway. Work is work. The schedule is all I need to concern myself with.

“You’ll be in 4202,” Miss Mary adds before turning away from the window.

* * *

Forty-two-oh-two is a dog. An MC-7 model built in 1968, it had already seen its better days when Greyhound sold it at auction in 1980. I’ve driven it more times than I can count. As the white man on the totem pole, I’m never allowed to drive anything built in the last thirty years. She’s serviceable as a commuter, when passengers need spend no more than an hour at a time in ’er—and never use the bathroom—but a two-day trip can be hell. Especially if it’s hot; the A/C barely works and the tiny toilet tank ripens in a hurry.

Whoever today’s client is, they’re no VIP, that’s for sure. And they’re definitely not Chinese. Hee Kwan would never stand for 4202 for any of his regulars. The only time I drive it on a gamblers’ turn is when I’m picking up Anglo customers from the South Bay.

I reach the pick-up point at 24th and Noe an hour early, which gives me time to scarf down a couple of breakfast sandwiches at Happy Donut down on Church Street. I also grab a coffee and a couple doughnuts for the road. Coffee is like blood to a bus driver. Too little of it flowing through your veins can be fatal.

I return to the bus a full half-hour before the scheduled pick-up only to find that two passengers have already boarded. It’s a poorly kept secret that coaches of this vintage don’t have door locks. Anyone who knows this can reach through the driver’s side window—which also doesn’t lock—and release the door. What the presence of these two passengers tells me, is that at least one of them is not a first time rider.

This doesn’t surprise me. What surprises me is that they are both elderly women. Not the usual breaking-and-entering suspects. It takes no effort at all to deduce that they’re also lesbians; I lived in the City for over a decade before my current exile in West Oakland began. I’ve known plenty of gay women. Somehow they tend to like me better than other straight men.

“Morning,” I say as I step up into the bus.

“What’s that?” the smaller of the two women calls out from about the fifteenth row.

“He said ‘good morning,’” her partner barks.

“Well he shouldn’t mumble,” the first one snaps back at her.

I drop my doughnuts on the driver’s seat and leave the two of them squabbling as I step back onto the sidewalk. I’m hoping the manifest isn’t packed with elderly passengers; I don’t want to spend the whole weekend shouting.

The next two passengers to arrive are much younger—mid-forties or so. They are also women. And they’re also lesbians, which sets me to wondering. It doesn’t take long for my suspicion to be confirmed: the tour has been organized by a travel agency called Now Voyagina, whose lesbian owner is among the arriving passengers.

It figures. Noe Valley should have been the first clue. On the flipside of the hill that separates it from the mostly gay-male Castro, Noe Valley is the preferred neighborhood of “Lumpies”—lesbian upwardly-mobile professionals—as well as the more traditional Yuppies. But the latter are more likely to have kids, so they rarely figure among the passengers on a gamblers’ getaway.

The woman in charge of this excursion introduces herself as J.T. If I didn’t know better, I could have easily mistaken her for a fifteen-year-old boy, at least from a distance. Cargo shorts, sockless Skechers, and a loose T-shirt covered by an unbuttoned, short-sleeved plaid sport shirt. None of it suggests her actual gender. A face full of piercings and arms covered in tattoos do nothing to make it any clearer.

“There’ll be twenty-seven of us,” she tells me after making a pass through the coach, checking names on her clipboard. “We’re waiting for eight more people.”

“Right,” I say. It’s all the same to me. The fewer the better though, so the bathroom takes less of a beating. I just hope they don’t stuff the tank with feminine hygiene products like many of the foreign women do.

“But if they’re not here by 7:15,” J.T. says, looking at her watch. We’re leaving without them.”

We settle in to wait. I take my seat, leaving J.T. at the curb to check the late arrivals in. It’s clear they don’t need my help in boarding; just offering the usual assist I’d give the ladies would likely earn me a punch in the nose. A straight man in San Francisco learns quickly to stay out of a lesbian’s face whenever possible.

It’s 7:30 when the last of the women is seated and I stand to announce the itinerary. Coach 4202 hasn’t had a working PA system since before my time, so I do my best to project—an uncomfortable necessity, due to my condition.

“Welcome to Giton Charter Service,” I say. I omit the usual form of address—Ladies—because I’ve been corrected more than once by feminists who insist they are not “ladies,” but “women”—or “womyn.”

“It’ll be about five hours to our destination today, so we’ll be making one stop in Sacramento for a stretch, a bathroom break, or a bite to eat—what have you.”

I pause when another squabble erupts between the old ladies near the back. “Will you please speak up?” the little one says as her partner tries to shush her.

I have a better idea. I walk down the aisle and turn back toward the front, standing just behind the row the two women occupy. There I repeat what I just told them, adding, “It will be a twenty-minute break.”

TJ interrupts. “Yeah, twenty minutes!” she shouts from the front row. “You hear that? We’re not gonna wait for stragglers, so you better watch the time.”

“That should put us into Stateline right about one o’clock, in time for lunch,” I conclude, walking back to my seat. “Relax. Have fun. Enjoy the trip.”

“What’s that?” Little Old Lady calls out from behind. “I missed that last part!”

As I pull the bus away from the curb and make my way to the Central Freeway, I’m already relishing this trip. Gimme a ’nighter over a turn any day, just to have a hotel room with a real bed, cable TV, and a full bathroom with tub and shower—all things I no longer enjoy as a resident of the Giton garage. Small luxuries, sure, but they mean the world to me. Funny how life messes with your perspective on things.

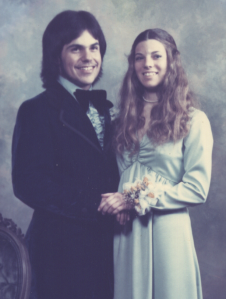

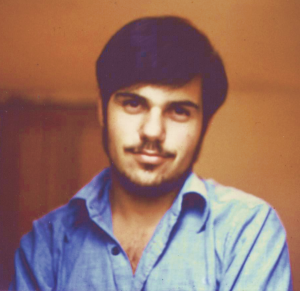

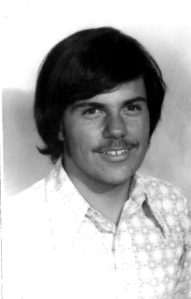

Click the image to watch the book trailer!

Click the image to watch the book trailer!